by Julia Fenton

The first time that I encountered the Great Toad Mother, I didn’t know who she was.

I saw her only through the lens that I had been taught: intriguing and silly-looking, at best; a metaphor for ugliness, for disgust. I heard the Toad Mother everywhere, not knowing that there was a Toad Mother.

I felt her in my body, and saw her in my dreams. I wrote angst-ridden poems that I did not understand, featuring a soup-pot or a cauldron, a bog, a desperate plea of invocation to Kind Mother Toad.

But as I got to know her, I found she wasn’t simply the slimy, warty familiar of the stereotypical sinister, warty witch.

Rather, she was the inspiration behind the hag in her literal sense – from the German for “woman of the hedge,” the one who crosses the hedgerow, who can enter into the world of spirits or the dead, and yet return.

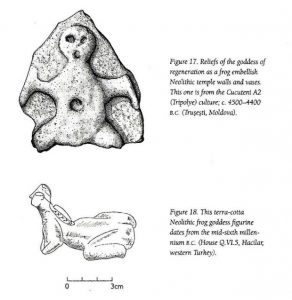

A decade or so after our first meeting, I’ve found that the Holy Toad has a long and mysterious history. Bone-engravings of frog-goddesses have been found in Europe dating back to the Upper Paleolithic.

image source: Gimbutas, Marija. (2001.) The Living Goddess. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 27.

image source: Gimbutas, Marija. (2001.) The Living Goddess. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 27.

To the ancient Egyptians, the Primordial Toad Mother was Heket, goddess of reproduction, childbirth, and death.

Closely associated with the river-floods that gave the land fertility, and with the resurrection of the god Osiris, Heket embodied the link between woman, water, reproduction and rebirth. Her hieroglyph was a frog.

The anthropomorphic toad goddess is seen also in Ragana, a Baltic goddess of death, divination, and rejuvenation, who is often described in the shape of a toad.

In this region, the toad goddess has been preserved in the image of the toad as a symbol of death, the use of “Toad!” as an expletive – and the simultaneous folk belief that placing a live toad on the skin can be used to heal wounds and growths.

Sheela na gig is the wide-eyed female figure who squats in a toadlike position and prominently bares and touches her vagina in the stonework of churches and castles throughout Britain, Ireland, and France.

Seeming out-of-place and utterly baffling from a patricentric/monotheistic perspective, she is one of the last surviving images of the Great Toad Mother in Christianized Europe: crouched naked on the doorframes of churches, reminding us that she is still alive.

Neolithic European pottery sometimes abbreviated the Toad Mother as the symbol “M” (see her squatted toady legs?) – a symbol which interestingly, in later Old Norse mythology became mannaz, the rune of mankind, not only in the patriarchal sense: humanity, the human condition.

For a long period of my life, unaware of the correlation between M and the toad, I became increasingly frustrated that I was continuously shown this same rune. (I know that to be human is devastatingly painful, what is your point?) Now I see it as a call from the Great Toad.

I’ve seen her, too, in perthro, the rune that is interpreted either as the dice cup of chance, or vagina of the goddess, depending who you ask.

Toads and Witches

The toad was immediately incorporated into the witch stereotypes that arose in the early modern era; the “witches’ brew” of Macbeth infamously lists toad as an ingredient.

Inquisition documents describe rites in which the witch is initiated by kissing or licking a toad, or drinking from a potion containing toad venom, and list toad venom as an ingredient of the ointments used to induce the experience of flying or shape-shifting.

According to German folklore, the toad prefers to live beneath the poison hemlock plant, sucking up the plant’s poison; hemlock was another infamous “flying herb.”

Anthropologists believe that the psychoactive nature of toad venom may play a role in its association with witchcraft.

All toads contain the toxic psychoactive substance bufotenine, where certain species such as Bufo alvarius are known to contain DMT, the consciousness-opening psychoactive molecule also found in South American Ayahuasca preparations.

Other sources record that in some South American indigenous cultures, they dried venom of toad and smoked it in a pipe, possibly in association with a toad deity.

Did ancient Toad Goddess cults use toad venom for magical purposes? No one knows for sure. But with this attribute, Mother Toad reminds us to open our minds to new dimensions of thought.

The Great Toad Metaphor

The toad lays her eggs in water – a universal symbol of womanhood. The young life-stages of the toad resemble the human fetus. The toad appears in the spring, a time of rejuvenation, of birth-festivals.

Anthropologists have also attributed this connection to the squatting position of women giving birth.

Some species of toad will eat their own cast-off skins. Some will eat toad eggs, or younger toads of their own species. Some are toxic to the touch.

Then, there are the wet and swampy areas where the toads dwell.

Bogs and other dark, mysterious bodies of water have long been regarded as holy places: the ritual spaces of ancient sacrificial cults, dwelling-places of the dead ancestors and of wild or malevolent spirits.

There is an air of danger and mystery: the swamp can lure you in and swallow you whole.

This is the place where the witch speaks to the death-goddess, the divine crone whose rejuvenating cauldron was the alder-groves where humans were sacrificed and where frogs and toads make their watery homes.

In Chinese folklore, a lunar eclipse results because the moon-toad swallows the moon. Once again, toad brings the darkness.

The toad is also closely related to the water lily in the mythology of cultures on multiple continents – and the water lily, in turn, is often used as a symbol of death and rebirth.

The swamp is the Cauldron of knowledge and inspiration, and so the toad is Cerridwen, who resurrects dead warriors in her cauldron and gives birth to the primeval poet. Death is rejuvenation.

To be cooked in a cauldron and then reborn is an image seen in shamanic traditions worldwide. The Toad Goddess is a teacher of shamans and witches, seers and visionaries. We are reborn out of the swamp.

In The Cauldron

She is not going to make this easy. She is the opposite of your ego. She is also the opposite of the love-and-light goddess whom I thought I worshipped. It is not quick. It’s not tearing off a band-aid. It’s a bubbling, boiling cauldron.

The Toad Mother leaves me in awe of the awesome beauty of my own helpless and insignificance.

Industrialized, consumerist society tries to bandage the emotional wounds that it creates, by telling us that we are all “special snowflakes.”

The Great Toad teaches that all snowflakes will melt, and go into the groundwater, and snow again. She also teaches us to be a part of the raging snowstorms and other forces of weather that shape our world – and that to be woman, to be witch, is to be the energy of the great ocean womb that can eat cities whole.

She is Kali, and Hecate, and Cerriddwen. Devouring and rebirthing. You can’t worship the toad mother and your own ego.

She will throw you back in the soup-pot. To be a witch is to be torn apart. She will cook you in her cauldron until the medicine is extracted from your bones.

Patriarchal monotheism is terrified of the Toad Mother.

She does not care about social beauty norms. She bares her vagina over the doorframe of the church. She is ugly, warty, slimy, toxic, psychedelic, cannibalistic, motherly, wise, and nurturing.

She shatters the illusion of human control that holds destructive social structures in place.

Lately, it has felt as though the world is falling apart, on a macrocosmic and microcosmic scale. As though, just as icebergs are melting and cities are burning, everyone I know seems to be in personal conflict.

Transformation and regeneration does not happen only on an individual level. Mother Toad is here, and she is already ripping at our bones, cooking our flesh.

Patriarchal society is not going to fix the ecological harm that has been done by misogyny against the Earth Mother.

It isn’t the war-gods who put the earth back together.

It’s the Holy Toad of rebirth, tearing us apart, remodeling us in her great cauldron-bog.

Unmaking is the price of wisdom. The world doesn’t need to praise the gods of love-and-light right now; it need the witches who have seen darkness and been reborn.

Now, more than ever, we need the energy of the Great Toad Mother. She tells it like it is.

Listen to her.

About the Author:

Julia Fenton is an herbalist, hedgewitch, poet, graduate student, seer, hearer, gardener, and maker of potions and ointments to promote radical earth-love and self-embodiment. You can find her, and her creations, in her garden of plant magic on tumblr.

Julia Fenton is an herbalist, hedgewitch, poet, graduate student, seer, hearer, gardener, and maker of potions and ointments to promote radical earth-love and self-embodiment. You can find her, and her creations, in her garden of plant magic on tumblr.

featured image – source

image source

image source image source

image source

Show Comments (0)