by Andrei Burke

David Lynch is a quintessential American filmmaker. His uncompromising individuality and exceptional vision make one of the most American filmmakers despite the fact that he has not made a film for a mainstream studio in over 30 years.

He possesses an outsider’s vision with an insider’s view, and his films possess the viewer in much the same way.

Lynch’s film and television work tear away the veil that separates conscious from unconscious.

Be it the criminal underbelly that lurks beneath the American Dream, the madness at the heart of moviemaking or the chaos crawling under the fabric of reality itself—Lynch’s films blur the boundaries of what is real and what only seems to be so, and reveals that we don’t actually know the difference.

His films are paintings of light doubling as portraits of shadows.

The films of David Lynch are not so much stories as they are puzzles. These puzzles are not meant to be solved as much as they are pondered—and it is through pondering that the whole of reality begins to reveal itself with each subsequent viewing and reflection.

You don’t exactly open up understanding with a David Lynch film—you open a portal. (Lynch’s films often even feature some object or set piece that acts as a portal: the radiator in Eraserhead, the ear in Blue Velvet, the cigarette burned sheet in INLAND EMPIRE).

Lynch depicts a world beyond mundane consensus reality. He uses the very language of narrative and cinema to transpose a greater reality in the here and now.

These films speak in the twilight language of a dreamer’s cinema, reveling in their phantasm populated by femme fatale succubi, psychotic gangsters, and secret societies running shadow realities beneath a crisp American nostalgia. A David Lynch film reveals the magic in the mundane.

FROM THE AMERICAN DREAM TO THE DREAM FACTORY (AND BEYOND)

David Lynch is as puzzling a man as his films: an honored Eagle Scout and meditation master, an Americana nostalgist and avant-garde filmmaker, a tradition-breaking genre purist.

He was born on January 20, 1946 in Missoula, Montana. His father was a research scientist working for the United States Department of Agriculture. Due to the nature of his father’s work, the Lynch family frequently moved around to rural spaces and bucolic towns across America.

After receiving the Boy Scouts’ highest honor of Eagle Scout, Lynch moved to Philadelphia to study painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

It was at PAFA, while producing the mixed media project Six Men Getting Sick, that Lynch switched his major from painting to film.

The transition from rural America to urban decay that Lynch experienced when he moved to Philadelphia left an impression that he has explored throughout his entire filmmaking career, starting with his debut film Eraserhead.

In the early 1970s, Lynch moved to Los Angeles to study filmmaking at the American Film Institute. At AFI, Lynch would produce his first feature film, the cult classic Eraserhead.

Another milestone of Lynch’s artistic career happened during his time at AFI: he began the daily practice of Transcendental Meditation. This period planted a seed that would grow into a career in which a master of his craft would produce provocative surreal films that probe into mystical states of consciousness.

Listed below are the essential films of David Lynch for the magically minded.

Eraserhead (1977)

Lynch’s debut film is also his most spiritual film, according the filmmaker himself: “No one understand when I say that [Eraserhead] is my most spiritual movie, but it is,” Lynch wrote in his 2006 book Catching the Big Fish.

Eraserhead sounds like a standard coming-of-age melodrama at first glance: a man deals with the pressures of adulthood and parenthood by escaping into a strange dream world where “everything is fine.”

However, Lynch shot Eraserhead in harsh contrasting black-and-white, setting his story in a decayed industrial wasteland where characters dwell in claustrophobic quarters with a premature mutant baby and a radiator that hides a fantasy cabaret.

Eraserhead is about the mundanity of life punctuated by the monstrosity of existence, and the imagination’s power to transform it into something beyond this world. By dwelling in darkness, Lynch reveals the light of the true self.

In Catching the Big Fish, Lynch gives a glimpse into the creative process behind Eraserhead:

“It was a struggle. So I got out my Bible and I started reading. And one day, I read a sentence… And then I saw the thing as a whole. And it fulfilled this vision for me, 100 percent… I don’t think I’ll ever say what that sentence was.”

(If you read the above statement between the lines, you’ll see that Lynch reveals a major secret to his entire film oeuvre)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UmyzYBeGrE8

Following Eraserhead, Lynch made two films for major studios: The Elephant Man and Dune.

Both films capture an undying nostalgia for old Hollywood that would predominate his later work—The Elephant Man being a reshaping of the Monster Movie genre of the 1930s, and Dune containing elements of the lush historical epics by the likes of Cecil B. Demille told by way surreal scifi melodrama.

Dune was a critical and commercial disaster that left Lynch with a bad taste for the real Hollywood in his mouth.

Blue Velvet (1986)

With Blue Velvet, Lynch was given creative freedom and final cut, and was able to begin exploring more fully the themes he first introduced in Eraserhead.

Much like Eraserhead, Blue Velvet at first sounds like a tawdry coming-of-age tale: a young man, visiting his small town home from college in the wake of his father’s illness, discovers that all is not as it appears while two women fight to be the girl of his dreams.

Blue Velvet shows the perversity that hides deep within those dreams. After finding a severed ear lying in a field, our all-American protagonist Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) is led into a surreal shadowscape ruled over by one of the most depraved psychopaths ever portrayed on film—the sadistic Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper in one of his greatest roles).

Jeffrey soon finds himself the object of masochistic nightclub singer Dorothy Vallens’ (Isabella Rossellini) affection—further complicating her already complicated relationship with Frank.

Meanwhile, Jeffrey maintains a mask of social acceptability, working in his father’s hardware store and going out for milkshakes with the girl next door (Sandy Williams, played by Laura Dern).

Lynch is not satirical or cynical about the gleaming surface of the American Dream; there is an honesty and sincerity in the way he portrays it. The small town surface has as much warmth and light as its underbelly does cold and darkness.

In its probing the nightmare depths that dwell beneath dreamy surfaces, Blue Velvet provides the framework of Lynch’s films to come. It’s presence is especially felt in his next project, the small town murder mystery television series Twin Peaks.

Twin Peaks (1990)

The cult television series Twin Peaks made David Lynch a household name. Conceived of with co-creator Mark Frost, Twin Peaks portrays the Federal investigation of the murder of a small town beauty queen.

This permeation of the macro into the micro (small town USA visited upon by the FBI) finds itself repeated over and over again through the entire series and its prequel film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, as we see the macrocosm of forces both angelic and demonic determine the microcosmic events of Twin Peaks.

Most of the mystical and supernatural elements of the show were influenced by co-creator Mark Frost’s interest in the Theosophical Society and the esoteric teachings of its founder Madame Blavatsky, as well as predominate students such as Alice Bailey and Dion Fortune.

The White and Black Lodges were influenced by Blavatsky’s concept of the Great White Brotherhood, an order of mystical beings who spread wisdom teachings to humankind.

The character Hawk mentions that his “people” believe in a being known as the Dweller on the Threshold, a concept Blavatsky lifted from the 19th century novel Zanoni.

The Dweller on the Threshold is a malevolent entity that spiritual seekers must cross on their path to perfection.

Below is a terrific analysis of the esoteric themes buried in Twin Peaks.

Lost Highway (1997)

Lost Highway is Lynch’s first film set in Los Angeles, and could be seen in the first of an informal trilogy of films that play with narrative, identity and time in a way never before witnessed in cinema.

In this film, Lynch portrays the sun drenched landscapes and decadent glamour of the Southland as a noirish Bardo. After s hip jazz musician is sentenced to death for the murder of his wife, he suffers a psychogenic fugue and wakes up in his jail cell as completely different person.

Upon being released, he lives life as a slacker auto mechanic living in with his parents in a tacky Los Angeles suburb—until elements of his formal life begin consuming the prosaic aspects of his assumed identity.

Lynch begins blurring the lines between reality and illusion in Lost Highway, in effect distorting his audience’s perception of space and time like few filmmakers have been able to do before or since—a theme he continued in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire.

A synchronicity related to this film: in Catching the Big Fish, Lynch claims to have been inspired to make Lost Highway by the OJ Simpson trial.

In a creepy case of life imitating art, the actor who portrayed the film’s elusive Mystery Man, Robert Blake, became the subject of his own media circus as he was tried and acquitted of the murder of his then-girlfriend eight years after the film’s release.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qZowK0NAvig

Mulholland Drive (2001)

Between Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, Lynch made a single film that stands apart in his oeuvre: the minimal masterpiece The Straight Story (1999).

While The Straight Story separates itself from most of Lynch’s work in its simplicity and straightforward narrative (get it?), it fits in through its small town charm giving way to cosmic transcendentalist themes.

But like the first bender right out rehab, Lynch got back to business-as-usual with Mulholland Drive.

With this film—the second in what could be called Lynch’s Bardo Noir Trilogy—Lynch takes the audience deeper down the rabbit hole that he opened with Lost Highway, moving from the hillside mansions that outline Los Angeles into the dark and shadowy spaces of Hollywood’s Dream Factory.

The story is simple: a failed actress dreams of the perfect life as she festers in the rotting remains of her career.

The execution is otherworldly: one woman dreams she is another woman suffering from amnesia, who may or may not be different person. The centerpiece of the film is Club Silencio, an oneiric vaudeville that exists at the veil between worlds, where everything is a tape recording. The scene recalls a passage of The Upanishads:

As long as man is overpowered by the darkness of ignorance, he is the slave of Nature and must accept whatever comes as the fruit of his thoughts and deeds. When he strays into the path of unreality, the Sages declare that he destroys himself; because he who clings to the perishable body and regards it as his true Self must experience death many times.

Worldly existence is but a tape recording of the true self. It may sound as an authentic artifact which can be repeated many times, but it is only a simulation of what is true. Every time the recording is played it deteriorates until all that is left is the silence of true self.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xrC3Bf-CvHU

Inland Empire (2006)

We’ve traveled along the lost highway, down Mulholland Drive, when we reach our final destination: Inland Empire. There is not much to be said about this film. It must be experienced.

Lynch uses digital video in a similar way that Orson Welles used celluloid more the 60 years prior when he made Citizen Kane: he deconstructs identity by disjointing time in a way that revolutionizes the way movies are made.

But Welles was tied down by the confines of the sound stage and 1940s film technology. Digital allowed Lynch an ease of mobility to move across varying layers of intersecting realities and timelines that celluloid could not deliver.

Inland Empire continues the Bardo Noir of Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, taking us deeper into the nightmares that inspire the illusionists who run the Dream Factory—all the way back to previous lives and even further to a time outside of time.

The viewer, as well as the film’s female lead (a once famous actress now hoping on a comeback role), is initiated into the plot by a strange visitor to her mansion. The visitor regails an old tale:

A little boy went out to play. When he opened his door, he saw the world. As he passed through the doorway, he caused a reflection. Evil was born. Evil was born, and followed the boy… and a variation. A little girl went out to play. Lost in the marketplace, as if half-born. Then, not through the marketplace – you see that, don’t you? – but through the alley behind the marketplace. This is the way to the palace. But it isn’t something you remember.

Lynch borrows the term “marketplace” from his guru, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who used it to describe the condition of ordinary human interactions that rob us of an authentic experience of the self.

By the end of the scene, time quite literally warps and the viewer is sent on a journey well beyond the bounds of the marketplace into a shattered hall of mirrors of time, memory, and identity.

“What 2001: A Space Odyssey did for outerspace, Inland Empire does for innerspace.” (via: http://www.amazon.com/David-Lynch-Swerves)

Following the release of Inland Empire, Lynch has been on an extended hiatus to run the David Lynch Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to spreading the teachings and practices of his guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Much like meditation, words fail to do justice the films of David Lynch. For the full experience you just need to sit down, shut up and open your eyes.

About the Author:

Andrei Burke is a poet and filmmaker living in the Los Angeles area. He holds degrees in both film and cultural studies. He has written for Ultraculture (ultraculture.org) and is soon launching the spirituality and lifestyle blog Love + Metta (loveandmetta.org).

Andrei Burke is a poet and filmmaker living in the Los Angeles area. He holds degrees in both film and cultural studies. He has written for Ultraculture (ultraculture.org) and is soon launching the spirituality and lifestyle blog Love + Metta (loveandmetta.org).

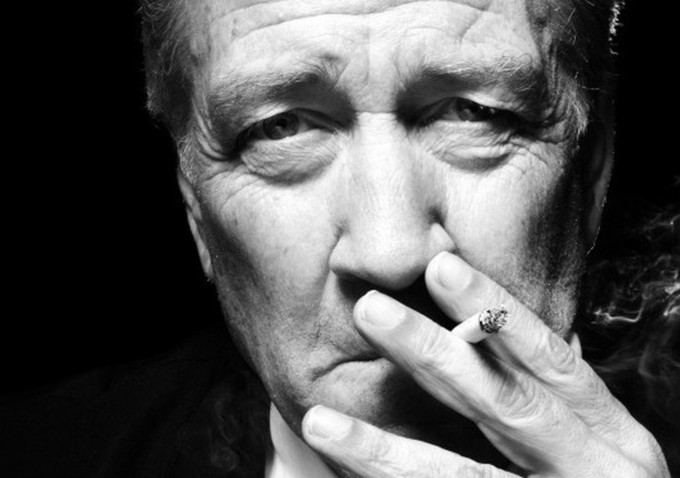

featured image – Source

Show Comments (2)

Zoltan

Dune is an genius movie. Full of insights, not only from physical side, but especially from mystical side, inner side. There are more details what can know only man who had such experiences. Very deep and very true – 7 days of unconscious, visions, deeper understanding after woke up, !!! places where cannot go or see any of the best clairvoyance (also the Mother not – its not only point to the Bible, but also deep, very deep true, what knows only “Consecrated”)!!! and many more…

Kim

Thank you for this post. I am a huge Twin Peaks fan and this look at Lynch was incredibly interesting. I’m now going to check out a few more of his movies. :)